Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a complex psychiatric condition that develops in certain individuals after experiencing a major traumatic event(1). Behavioral symptoms of PTSD include re-experiencing the trauma, avoidance behavior, mood alternation, and hyperarousal(2). A large percentage of individuals with PTSD will also experience chronic pain, sleep disorders, depression, anxiety, and other related mental health issues(2).

The culmination of these symptoms increases the risk of diseases such as obesity, diabetes, neurocognitive disorders, dementia, cardiovascular disease, and autoimmune disorders as well(3-7). Recent evidence suggests oxidative stress and inflammation to be part of this stress-perpetuating syndrome(8).

The negative impact that such symptoms and risks can make on one’s quality of life makes it clear that individuals with PTSD require safe, effective treatment options. Unfortunately, less than half of patient receiving traditional psychosocial treatments gain clinically meaningful improvements, and many continue to have residual symptoms(9-10).

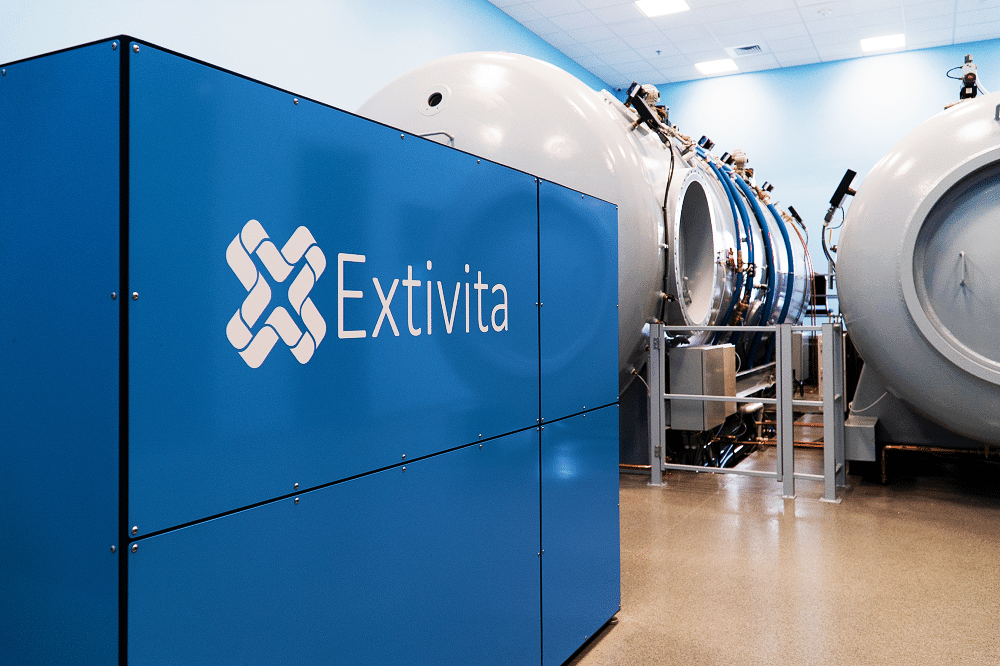

We strongly recommend hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) and neurofeedback therapy for individuals with PTSD. Nutritional IV therapy, pulsed-electromagnetic field (PEMF) therapy, and infrared sauna therapy can all help PTSD as adjunctive therapies.

Extivita Therapies for PTSD:

Extivita Therapies for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder:

Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy

Neurofeedback

Supplements

Nutritional IV Therapy

Pulsed Electromagnetic Field Therapy

Listen to Dan’s experience with Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy to treat PTSD

Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy for Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder:

The consequences of oxidative stress and inflammation include accelerated cellular aging as well as increased risk of neurological, cardiovascular, and respiratory diseases. Taken together, the effects of increased disease risk increase the physical and emotional burden of those with PTSD(13).

Thankfully, HBOT has been shown to inhibit many of the same proinflammatory cytokines (chemical messengers) that are elevated in PTSD, while also increasing anti-inflammatory/antioxidant gene expression(14). By doing so, HBOT may improve some of the chemical imbalances that can cause serious damage to those with PTSD. Lastly, PTSD has also been associated with patients who have suffered from traumatic brain injury (TBI), and HBOT is known to have significant benefits for those with TBIs (see our TBI page). (4,7).

Effects of HBOT on PTSD:

New Blood Vessel Formation

Increased Stem Cell Activity

Decreased Inflammation

Neurofeedback for PTSD:

Neurofeedback therapy has strong potential as an effective, non-invasive therapy for those with PTSD. Individuals with PTSD are believed to have a degree of dysfunction in two important neural networks: the salience network (SN) and the default mode network (DMN) (10-11). Normalizing these networks through neurofeedback has been shown to significantly improve symptoms of PTSD (12-16).

To normalize these networks, neurofeedback protocols for PTSD typically focus on 1) reducing theta and high-beta while increasing low-beta activity(14, 17) or 2) decreasing alpha activity(12,13). Both protocols have shown to significantly improve symptoms of PTSD and improve emotional regulation after 20-40 neurofeedback sessions.

IV Therapy for PTSD:

Both Glutathione and Vitamin C are powerful antioxidants which can help decrease reactive oxygen species, oxidative stress, and inflammation in patients who suffer from PTSD. One of the primary issues in PTSD is the repeated pattern of re-experiencing the traumatic event, which results in chronic activation of the body’s stress response(23). Additionally, the sleep disruption, hypervigilance, anger, anxiety and dysphoria that most people with PTSD experience also activate the stress response. The net effect of this is hyperactivation of the stress network resulting in in oxidative damage(23).

The Myer’s Cocktail IV contains Vitamin C and other nutrients which have been shown to counteract increases in stress hormones(24-25). Levels of Glutathione, the master antioxidant, are imbalanced in patients with PTSD (26). Our Glutathione IV can increase Glutathione levels in the body to reduce oxidative stress and enhance cellular detoxification. We recommend both the Myer’s Cocktail IV and Glutathione IV as part of a multi-modal therapy for individuals with PTSD.

Pulsed Electromagnetic Field Therapy for PTSD:

Pulsed-electromagnetic field therapy (PEMF) can be used as a support therapy for those with PTSD. The PEMF device we use at Extivita, called BEMER, delivers low frequency, pulsed magnetic signals to all your muscles and tissues. This results in improved microcirculation, as well as increased oxygen and nutrient delivery to much needed areas of the body. Additionally, PEMF has been shown to reduce levels of inflammation, which is a primary culprit in PTSD pathology(27, 8). BEMER also has an accessory called the B-pad which can be utilized to target specific regions. In cases of neurological concerns like PTSD, we can position the B-pad over the individuals head to maximize PEMF’s therapeutic benefits.

News & Research for PTSD:

9/11 Tribute Honoring All Who Defended America

In this 9/11 tribute, Extivita honors all service members who have defended our country & highlights the unfortunate truth about veteran suicide. Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy is breathing new life into injured veterans and saving lives. If you know someone suffering...

Gaining Independence from Suicidal Ideation

Treat Brain Wounds with Hyperbaric Oxygenation and other Alternative Therapies "VA’s top clinical priority is preventing suicide among all Veterans — including those who do not, and may never, seek care within the VA health care...

A Case Series of 39 United States Veterans with Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Treated with Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy

Abstract: Importance: The Defense and Veterans Brain Injury Center reported 358,088 mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI) among U.S. service members worldwide between the years 2000 and 2020. Veterans with mTBI have higher rates of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD),...

References

- NIMH » Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/post-traumatic-stress-disorder-ptsd#part_155467. Accessed 2 June 2021.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edn. American Psychiatric Publishing, Arlington, VA, 2013.

- Michopoulos, Vasiliki, et al. “Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Metabolic Disorder in Disguise?” Experimental Neurology, vol. 284, no. Pt B, Oct. 2016, pp. 220–29. PubMed, doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2016.05.038.

- Mellon, Synthia H., et al. “Metabolism, Metabolomics, and Inflammation in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.” Biological Psychiatry, vol. 83, no. 10, May 2018, pp. 866–75. PubMed, doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.02.007.

- Edmondson, Donald, et al. “Posttraumatic Stress Disorder and Risk for Coronary Heart Disease: A Meta-Analytic Review.” American Heart Journal, vol. 166, no. 5, Nov. 2013, pp. 806–14. PubMed, doi:10.1016/j.ahj.2013.07.031.

- O’Donovan, Aoife, et al. “Elevated Risk for Autoimmune Disorders in Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder.” Biological Psychiatry, vol. 77, no. 4, Feb. 2015, pp. 365–74. PubMed, doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2014.06.015.

- Song, Huan, et al. “Association of Stress-Related Disorders With Subsequent Autoimmune Disease.” JAMA, vol. 319, no. 23, June 2018, pp. 2388–400. PubMed, doi:10.1001/jama.2018.7028.

- Miller, Mark W et al. “Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Neuroprogression in Chronic PTSD.” Harvard review of psychiatry vol. 26,2 (2018): 57-69. doi:10.1097/HRP.0000000000000167

- Bradley, Rebekah, et al. “A Multidimensional Meta-Analysis of Psychotherapy for PTSD.” The American Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 162, no. 2, Feb. 2005, pp. 214–27. PubMed, doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.214.

- Jonas, Daniel E., et al. Psychological and Pharmacological Treatments for Adults With Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US), 2013. PubMed, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK137702/.

- Passos, Ives Cavalcante et al. “Inflammatory markers in post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression.” The lancet. Psychiatry vol. 2,11 (2015): 1002-12. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00309-0

- Miller, Mark W et al. “Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Neuroprogression in Chronic PTSD.” Harvard review of psychiatry vol. 26,2 (2018): 57-69. doi:10.1097/HRP.0000000000000167

- Neigh, Gretchen N, and Fariya F Ali. “Co-morbidity of PTSD and immune system dysfunction: opportunities for treatment.” Current opinion in pharmacology vol. 29 (2016): 104-10. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2016.07.011

- Godman, Cassandra A et al. “Hyperbaric oxygen treatment induces antioxidant gene expression.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences vol. 1197 (2010): 178-83. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05393.x

- Szeszko, Philip R., and Rachel Yehuda. “Magnetic Resonance Imaging Predictors of Psychotherapy Treatment Response in Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder: A Role for the Salience Network.” Psychiatry Research, vol. 277, July 2019, pp. 52–57. ScienceDirect, doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2019.02.005.

- Akiki, Teddy J., et al. “Default Mode Network Abnormalities in Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Novel Network-Restricted Topology Approach.” NeuroImage, vol. 176, Aug. 2018, pp. 489–98. ScienceDirect, doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.05.005.

- Ros, Tomas, et al. “Mind over Chatter: Plastic up-Regulation of the FMRI Salience Network Directly after EEG Neurofeedback.” NeuroImage, vol. 65, Jan. 2013, pp. 324–35. ScienceDirect, doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.09.046.

- Kluetsch, R. C., et al. “Plastic Modulation of PTSD Resting-State Networks and Subjective Wellbeing by EEG Neurofeedback.” Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, vol. 130, no. 2, 2014, pp. 123–36. Wiley Online Library, doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12229.

- Kolk, Bessel A. van der, et al. “A Randomized Controlled Study of Neurofeedback for Chronic PTSD.” PLOS ONE, vol. 11, no. 12, Public Library of Science, Dec. 2016, p. e0166752. PLoS Journals, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0166752.

- Nicholson, Andrew A., et al. “Intrinsic Connectivity Network Dynamics in PTSD during Amygdala Downregulation Using Real-Time FMRI Neurofeedback: A Preliminary Analysis.” Human Brain Mapping, vol. 39, no. 11, 2018, pp. 4258–75. Wiley Online Library, doi:10.1002/hbm.24244.

- Rogel, Ainat, et al. “The Impact of Neurofeedback Training on Children with Developmental Trauma: A Randomized Controlled Study.” Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, vol. 12, no. 8, Educational Publishing Foundation, 2020, pp. 918–29. APA PsycNET, doi:10.1037/tra0000648.

- Gapen, Mark, et al. “A Pilot Study of Neurofeedback for Chronic PTSD.” Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, vol. 41, no. 3, Sept. 2016, pp. 251–61. Springer Link, doi:10.1007/s10484-015-9326-5.

- Miller, Mark W et al. “Oxidative Stress, Inflammation, and Neuroprogression in Chronic PTSD.” Harvard review of psychiatry vol. 26,2 (2018): 57-69. doi:10.1097/HRP.0000000000000167

- S. Brody, R. Preut, K. Schommer, T.H. Schürmeyer A randomized controlled trial of high dose ascorbic acid for reduction of blood pressure, cortisol, and subjective responses to psychological stress Psychopharmacology (Berl), 159 (2002), pp. 319-324, 10.1007/s00213-001-0929-6

- Peters, E M et al. “Vitamin C supplementation attenuates the increases in circulating cortisol, adrenaline and anti-inflammatory polypeptides following ultramarathon running.” International journal of sports medicine vol. 22,7 (2001): 537-43. doi:10.1055/s-2001-17610

- Michels L, Schulte-Vels T, Schick M, O’Gorman RL, Zeffiro T, Hasler G, et al. Prefrontal GABA and glutathione imbalance in posttraumatic stress disorder: preliminary findings. Psychiatry Res. 2014;224(3):288–95.

- Ross, Christina L., et al. “The Use of Pulsed Electromagnetic Field to Modulate Inflammation and Improve Tissue Regeneration: A Review.” Bioelectricity, vol. 1, no. 4, Mary Ann Liebert, Inc., publishers, Dec. 2019, pp. 247–59. liebertpub.com (Atypon), doi:10.1089/bioe.2019.0026.