Dementia

Dementia is a general term referring to several neurological disorders that result in cognitive impairment. More specifically, dementia is characterized by a decline one or more of the following cognitive domains: learning and memory, language, executive function, complex attention, perceptual-motor skill, and social cognition(1). Deficits must be significant enough to compromise activities of daily living and independence. It is important to mention that, while the most common risk factor for dementia is age, it is not a normal part of aging(1).

There are multiple types of dementia. The most common type of dementia is Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), a neurodegenerative disease that is responsible for 60% – 80% of dementia cases(1, 2). The second most common cause of dementia is vascular dementia (VD), which is a progressive neurological disease. Other types dementia includes frontotemporal dementia, Lewy body dementia (neurodegenerative) and mixed dementia (progressive)(1, 2).

Extivita Therapies for Dementia:

Extivita Therapies Dementia:

Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy

Neurofeedback

Supplements

Nutritional IV Therapy

Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy for Dementia:

In terms of vascular dementia (VD), one mechanism by which HBOT can protect against cognitive decline is by increasing a neuroprotective peptide called Humanin. Humanin levels have been shown to decrease in AD and normal aging, while higher serum levels of Humanin are positively correlated with better cognitive function(8, 9). A meta-analysis that included 1,975 total VD patients concluded that HBOT can be a safe, effective adjunct treatment for vascular dementia(10). For detailed information on HBOT and Alzheimer’s disease, see our Alzheimer’s page.

Effects of HBOT on Dementia:

New Blood Vessel Formation

Increased Stem Cell Activity

Decreased Inflammation

Neurofeedback for Dementia:

There are many studies that support Neurofeedback’s ability to significantly reduce cognitive impairment in the elderly population. Research reveals that individuals with Alzheimer’s disease (the leading type of dementia) have decreased alpha wave activity and increased delta and theta wave activity(10). Neurofeedback protocols that train the brain to correct these imbalances have shown to improve processing speed, executive function, and memory(11, 12, 13).

While there are few studies examining Neurofeedback and other forms of dementia, there are many studies that show benefits for mild cognitive impairment (MCI), a symptomatic phase that often leads to dementia. Increasing SMR activity while reducing theta activity can improve many cognitive categories in elderly individuals with MCI(14). Additionally, increasing alpha activity has been shown to improve memory in those with MCI, while increasing beta is correlated with improvement in attention and many other cognitive domains(15, 16, 17). For more information on Neurofeedback and Alzheimer’s disease, see our Alzheimer’s page.

IV Therapy for Dementia:

Mild cognitive decline (MCI), which typically leads to some form of dementia, is known to involve elevated oxidative stress in the brain(18). Additionally, oxidative stress is increased in those who already have types of dementia such as vascular dementia (VD) and Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Both Vitamin C, which is included in the Myer’s IV, and glutathione are powerful antioxidants that 1) may reduce the risk of developing VD or AD and 2) can reduce oxidative stress in patients who already have VD or AD(18, 19). Additionally, levels of Vitamin B12 and magnesium, both of which are in the Myer’s IV, are typically low in people with dementia, especially those with AD(20, 21, 22). We recommend both the Myer’s IV and glutathione IV to patients who have or are at risk of developing dementia.

News & Research for Dementia:

Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy shown to heal invisible injuries

BURLEY, Idaho (KMVT/KSVT) — A recent study showed for those with traumatic brain injuries, using hyperbaric oxygen therapy resulted in increased blood flow and more activity in the brain in areas that had been damaged from the injury. At the Health Oxygen Spa in...

Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy May Reverse Dementia Development

A research team in Israel has succeeded in reversing brain trauma using hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT). This is the first time in the scientific world that non-drug therapy has been proven effective in preventing the core biological processes responsible for the...

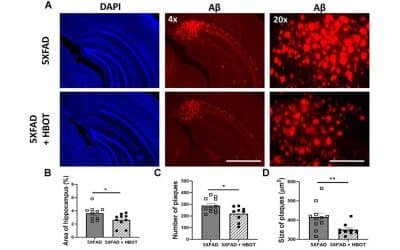

Hyperbaric oxygen therapy alleviates vascular dysfunction and amyloid burden in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model and in elderly patients

Abstract Vascular dysfunction is entwined with aging and in the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease (AD) and contributes to reduced cerebral blood flow (CBF) and consequently, hypoxia. Hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) is in clinical use for a wide range of medical...

References

- “What Is Dementia? Symptoms, Types, and Diagnosis.” National Institute on Aging, http://www.nia.nih.gov/health/what-dementia-symptoms-types-and-diagnosis. Accessed 26 Oct. 2020.

- “Changes in the Brain: 10 Types of Dementia.” Healthline, 5 Jan. 2017, https://www.healthline.com/health/types-dementia.

- Carney, Amy Y. “Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy: An Introduction.” Critical Care Nursing Quarterly, vol. 36, no. 3, Sept. 2013, pp. 274–279. journals.lww.com, doi:10.1097/CNQ.0b013e318294e936.

- Tal, Sigal, et al. “Hyperbaric Oxygen May Induce Angiogenesis in Patients Suffering from Prolonged Post-Concussion Syndrome Due to Traumatic Brain Injury.” Restorative Neurology and Neuroscience, vol. 33, no. 6, IOS Press, Jan. 2015, pp. 943–51. content.iospress.com, doi:10.3233/RNN-150585.

- Choudhury, Ryan. “Hypoxia and Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy: A Review.” International Journal of General Medicine, vol. Volume 11, Nov. 2018, pp. 431–42. ResearchGate, doi:10.2147/IJGM.S172460.

- Shapira, Ronit, Beka Solomon, Shai Efrati, Dan Frenkel, and Uri Ashery. “Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy Ameliorates Pathophysiology of 3xTg-AD Mouse Model by Attenuating Neuroinflammation.” Neurobiology of Aging 62 (2018): 105–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.10.007.

- Thom, Stephen R. “Hyperbaric Oxygen – Its Mechanisms and Efficacy.” Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, vol. 127, no. Suppl 1, Jan. 2011, pp. 131S-141S. PubMed Central, doi:10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181fbe2bf.

- Lee, Changhan, et al. “Humanin: A Harbinger of Mitochondrial-Derived Peptides?” Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 24, no. 5, May 2013, pp. 222–28. ScienceDirect, doi:10.1016/j.tem.2013.01.005.

- Xu, Yuzhen, et al. “Protective Effect of Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy on Cognitive Function in Patients with Vascular Dementia.” Cell Transplantation, vol. 28, no. 8, SAGE Publications Inc, Aug. 2019, pp. 1071–75. SAGE Journals, doi:10.1177/0963689719853540.

- You, Q, Li, L, Xiong, SQ, Yan, YF, Li, D, Yan, NN, Chen, HP, Liu, YP. Meta-Analysis on the Efficacy and Safety of Hyperbaric Oxygen as Adjunctive Therapy for Vascular Dementia. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019;11:86.

- Lizio, Roberta, et al. “Electroencephalographic Rhythms in Alzheimer’s Disease.” International Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease, vol. 2011, Hindawi, 12 May 2011, p. e927573, doi:https://doi.org/10.4061/2011/927573.

- Angelakis, Efthymios, et al. “EEG Neurofeedback: A Brief Overview and an Example of Peak Alpha Frequency Training for Cognitive Enhancement in the Elderly.” The Clinical Neuropsychologist, vol. 21, no. 1, Jan. 2007, pp. 110–29. PubMed, doi:10.1080/13854040600744839.

- Luijmes, Robin E., et al. “The Effectiveness of Neurofeedback on Cognitive Functioning in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease: Preliminary Results.” Neurophysiologie Clinique/Clinical Neurophysiology, vol. 46, no. 3, June 2016, pp. 179–87. ScienceDirect, doi:10.1016/j.neucli.2016.05.069.

- Marlats, Fabienne, et al. “SMR/Theta Neurofeedback Training Improves Cognitive Performance and EEG Activity in Elderly With Mild Cognitive Impairment: A Pilot Study.” Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience, vol. 12, June 2020. PubMed Central, doi:10.3389/fnagi.2020.00147.

- Lavy, Yotam, et al. “Neurofeedback Improves Memory and Peak Alpha Frequency in Individuals with Mild Cognitive Impairment.” Applied Psychophysiology and Biofeedback, vol. 44, no. 1, 2019, pp. 41–49. PubMed, doi:10.1007/s10484-018-9418-0.

- Jang, Jung-Hee, et al. “Beta Wave Enhancement Neurofeedback Improves Cognitive Functions in Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment.” Medicine, vol. 98, no. 50, Dec. 2019. PubMed Central, doi:10.1097/MD.0000000000018357.

- Beta Neurofeedback Training Improves Attentional Control in the Elderly – Jacek Bielas, Łukasz Michalczyk, 2020. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0033294119900348. Accessed 26 Oct. 2020.

- Pocernich, Chava B., and D. Allan Butterfield. “Elevation of Glutathione as a Therapeutic Strategy in Alzheimer Disease.” Biochimica et Biophysica Acta, vol. 1822, no. 5, May 2012, pp. 625–30. PubMed Central, doi:10.1016/j.bbadis.2011.10.003.

- Paleologos, Michael, et al. “Cohort study of vitamin C intake and cognitive impairment.” American Journal of Epidemiology, vol. 148, no. 1, Oxford Academic, July 1998, pp. 45–50. academic.oup.com, doi:10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009559.

- Chui, Dehau, et al. “Magnesium in Alzheimer’s Disease.” Magnesium in the Central Nervous System, edited by Robert Vink and Mihai Nechifor, University of Adelaide Press, 2011. PubMed, http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507256/.

- Morris, Martha Clare, et al. “Thoughts on B-Vitamins and Dementia.” Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease : JAD, vol. 9, no. 4, Aug. 2006, pp. 429–33.

- Malaguarnera, Mariano, et al. “Homocysteine, Vitamin B12 and Folate in Vascular Dementia and in Alzheimer Disease.” Clinical Chemistry and Laboratory Medicine, vol. 42, no. 9, 2004, pp. 1032–35. PubMed, doi:10.1515/CCLM.2004.208.