Depression

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is one of the most common mood disorders in the United States. Although there are many possible symptoms, depression is typically characterized by persistent feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and loss of motivation(1). The treatment of depression is incredibly important both for the health of your body, and the quality of your life.

Currently, the main treatment for depression is a combination of antidepressants and psychotherapy (“talk-therapy”). Unfortunately, about only 20% of depressed individuals experience symptom improvement with antidepressant medication(2). We highly recommend neurofeedback therapy for depression, especially for those who do not respond well to conventional treatment, or those looking for a a therapy with long-lasting benefits.

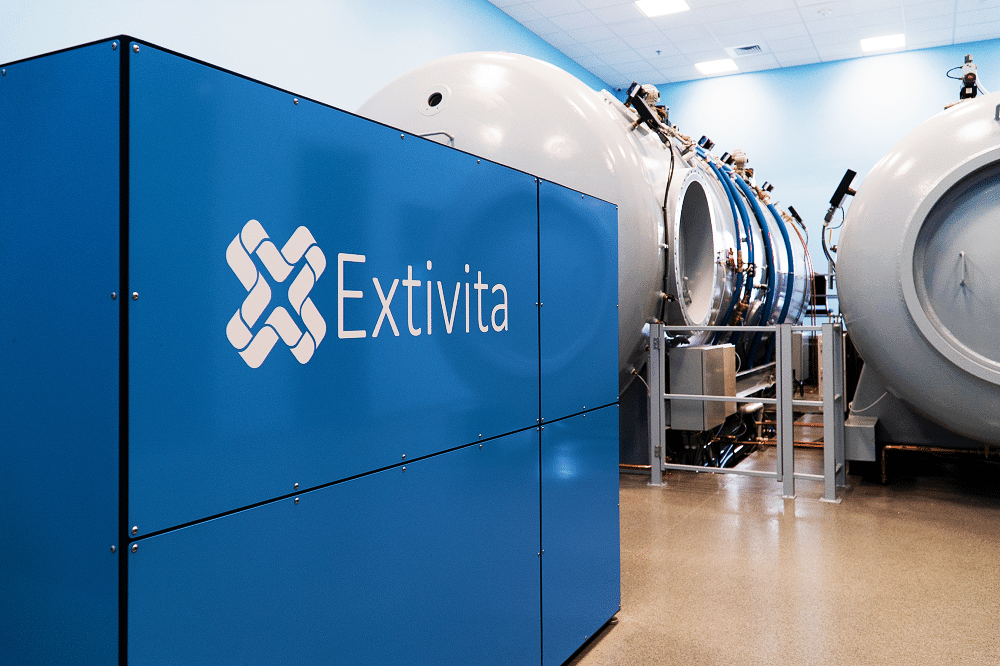

Extivita Therapies for Depression:

Extivita Therapies Depression:

Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy

Neurofeedback

Supplements

Nutritional IV Therapy

Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy for Depression:

Additionally, studies have successfully decreased depressive symptoms using anti-inflammatory medication (5). HBOT has proven anti-inflammatory effects, giving it strong potential as a low-risk therapy for those with depression(6-9).

Decreased Inflammation

Neurofeedback for Depression:

Neurofeedback protocols for depression typically focus on increasing brain activity in the left frontal lobe(10). Many people with depression have elevated alpha (8-12Hz) activity in the left frontal lobe, which can suppress faster brain waves necessary for increased brain activation(10). The left frontal lobe is associated with positive emotions and approach behavior, so a decrease of activity here can cause a person to focus less on positive emotions and more on negative emotions and withdrawal behavior(11-12). While decreasing left frontal alpha is the most common protocol for depression, neurofeedback protocol will be based heavily on one’s qEEG brain map, behavioral assessment, and neurofeedback consultation.

Common EEG Abnormalities in Depression:

- More alpha (8-12Hz) activity in the left frontal lobe compared to the right frontal lobe(3)

- Increased theta to beta ratio in the frontal lobe(3)

IV Therapy for Depression:

We recommend the Myer’s Cocktail IV and Glutathione IV for depression due to their antioxidant effects, as well as the NAD+ IV due to its protective effects on DNA and mitochondria. Oxidative stress, which causes cellular damage and inflammation, is known to be increased in those with depression(13-15). Vitamin C (a major component of the Myer’s Cocktail IV) and Glutathione are both powerful antioxidants that decrease levels of oxidative stress by eliminating reactive oxygen species(16-17). Additionally, low levels of Magnesium and certain B Vitamins (both of which are in the Myer’s Cocktail IV) have been associated with depression(18-21). Lastly, NAD+ has protective effects on DNA and mitochondria, both of which are likely damaged in those with depression(22-24).

News & Research for Depression:

Revolutionizing Stroke Recovery: Veteran’s Journey with HBOT

During a stroke, blood flow to parts of the brain is cut off, depriving brain cells of oxygen, which leads to tissue damage and loss of function. Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy (HBOT) offers a beacon of hope in such scenarios. By delivering oxygen under increased pressure,...

Stroke Recovery: Britney’s Recovery with HBOT

Britney Thomas's story is a testament to the power of hope, determination, and advanced medical treatment. After experiencing a life-altering stroke at a young age, Britney's journey with hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT) at UAB Medicine showcases not just her personal...

Treating chronic-stage stroke with hyperbaric oxygen therapy

Mohammed Elamir (The Villages, USA) and Amir Hadanny (Be’er Ya’akov, Israel) mark this year’s Stroke Awareness Month by discussing hyperbaric oxygen therapy (HBOT)—an emerging approach that they believe could break new ground in post-stroke recovery.Every year, more...

References

- NIMH » Depression. https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/depression/index.shtml. Accessed 19 Oct. 2020.

- Information, National Center for Biotechnology, et al. “Depression: How Effective Are Antidepressants?” InformedHealth.Org [Internet], Institute for Quality and Efficiency in Health Care (IQWiG), 2020. www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK361016/.

- Howren, M. Bryant, et al. “Associations of Depression with C-Reactive Protein, IL-1, and IL-6: A Meta-Analysis.” Psychosomatic Medicine, vol. 71, no. 2, Feb. 2009, pp. 171–86. PubMed, doi:10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181907c1b.

- Setiawan, Elaine, et al. “Role of Translocator Protein Density, a Marker of Neuroinflammation, in the Brain during Major Depressive Episodes.” JAMA Psychiatry, vol. 72, no. 3, Mar. 2015, pp. 268–75. PubMed, doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.2427.

- Köhler, Ole, et al. “Effect of Anti-Inflammatory Treatment on Depression, Depressive Symptoms, and Adverse Effects: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Clinical Trials.” JAMA Psychiatry, vol. 71, no. 12, Dec. 2014, pp. 1381–91. PubMed, doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1611.

- Benson, R. M., et al. “Hyperbaric Oxygen Inhibits Stimulus-Induced Proinflammatory Cytokine Synthesis by Human Blood-Derived Monocyte-Macrophages.” Clinical and Experimental Immunology, vol. 134, no. 1, Oct. 2003, pp. 57–62. PubMed Central, doi:10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02248.x.

- Lin, Kao-Chang, et al. “Attenuating Inflammation but Stimulating Both Angiogenesis and Neurogenesis Using Hyperbaric Oxygen in Rats with Traumatic Brain Injury.” The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, vol. 72, no. 3, Mar. 2012, pp. 650–59. PubMed, doi:10.1097/TA.0b013e31823c575f.

- Godman, Cassandra A., et al. “Hyperbaric Oxygen Treatment Induces Antioxidant Gene Expression.” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, vol. 1197, June 2010, pp. 178–83. PubMed, doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05393.x.

- Shapira, Ronit, et al. “Hyperbaric Oxygen Therapy Ameliorates Pathophysiology of 3xTg-AD Mouse Model by Attenuating Neuroinflammation.” Neurobiology of Aging, vol. 62, Feb. 2018, pp. 105–19. ScienceDirect, doi:10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2017.10.007.

- Dias, Álvaro Machado, and Adrian van Deusen. “A New Neurofeedback Protocol for Depression.” The Spanish Journal of Psychology, vol. 14, no. 1, May 2011, pp. 374–84. DOI.org (Crossref), doi:10.5209/rev_SJOP.2011.v14.n1.34.

- Davidson, Richard J. “Affective Style and Affective Disorders: Perspectives from Affective Neuroscience.” Cognition and Emotion, vol. 12, no. 3, Routledge, May 1998, pp. 307–30. Taylor and Francis+NEJM, doi:10.1080/026999398379628.

- Hammond, D. Corydon. “Neurofeedback Treatment of Depression and Anxiety.” Journal of Adult Development, vol. 12, no. 2, Aug. 2005, pp. 131–37. Springer Link, doi:10.1007/s10804-005-7029-5.

- Bhatt, Shvetank, et al. “Role of Oxidative Stress in Depression.” Drug Discovery Today, vol. 25, no. 7, July 2020, pp. 1270–76. ScienceDirect, doi:10.1016/j.drudis.2020.05.001.

- Black, Catherine N., et al. “Is Depression Associated with Increased Oxidative Stress? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Psychoneuroendocrinology, vol. 51, Jan. 2015, pp. 164–75. ScienceDirect, doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.09.025.

- Rawdin, B. J., et al. “Dysregulated Relationship of Inflammation and Oxidative Stress in Major Depression.” Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, vol. 31, July 2013, pp. 143–52. ScienceDirect, doi:10.1016/j.bbi.2012.11.011.

- Traber, Maret G., and Jan F. Stevens. “Vitamins C and E: Beneficial Effects from a Mechanistic Perspective.” Free Radical Biology & Medicine, vol. 51, no. 5, Sept. 2011, pp. 1000–13. PubMed Central, doi:10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.05.017.

- Forman, Henry Jay, et al. “Glutathione: Overview of Its Protective Roles, Measurement, and Biosynthesis.” Molecular Aspects of Medicine, vol. 30, no. 1–2, 2009, pp. 1–12. PubMed Central, doi:10.1016/j.mam.2008.08.006.

- Tarleton, Emily K., and Benjamin Littenberg. “Magnesium Intake and Depression in Adults.” The Journal of the American Board of Family Medicine, vol. 28, no. 2, American Board of Family Medicine, Mar. 2015, pp. 249–56. www.jabfm.org, doi:10.3122/jabfm.2015.02.140176.

- Serefko, Anna, et al. “Magnesium and Depression.” Magnesium Research, vol. 29, no. 3, Sept. 2016, pp. 112–19. www.jle.com, doi:10.1684/mrh.2016.0407.

- Hvas, Anne-Mette, et al. “Vitamin B6 Level Is Associated with Symptoms of Depression.” Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, vol. 73, no. 6, Karger Publishers, 2004, pp. 340–43. www.karger.com, doi:10.1159/000080386.

- Bell, Iris R., et al. “B Complex Vitamin Patterns in Geriatric and Young Adult Inpatients with Major Depression.” Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, vol. 39, no. 3, 1991, pp. 252–57. Wiley Online Library, doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1991.tb01646.x.

- Increased 8-Hydroxy-Deoxyguanosine, a Marker of Oxidative Damage to DNA, in Major Depression and Myalgic Encephalomyelitis / Chronic Fatigue Syndrome – PubMed. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20035260/. Accessed 12 Mar. 2021.

- Czarny, Piotr, et al. “Elevated Level of DNA Damage and Impaired Repair of Oxidative DNA Damage in Patients with Recurrent Depressive Disorder.” Medical Science Monitor : International Medical Journal of Experimental and Clinical Research, vol. 21, Feb. 2015, pp. 412–18. PubMed Central, doi:10.12659/MSM.892317.

- Chang, Cheng-Chen, et al. “Mitochondria DNA Change and Oxidative Damage in Clinically Stable Patients with Major Depressive Disorder.” PLOS ONE, vol. 10, no. 5, Public Library of Science, May 2015, p. e0125855. PLoS Journals, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0125855.